The growth of a city is usually defined by years of construction, destruction, and reconstruction. Over time, a city will evolve due to the demands placed on it, demands caused by shifting economic, political, and cultural trends.

The Back Bay, however, didn’t have the luxury of time to complete this type of development. Since it was a landfill, the whole of Back Bay was constructed at one time and for one purpose. That is, it wasn’t just land that was occupied over time. Rather, planners knew exactly how big the area was going to be. They already knew how each block was going to be shaped and what purpose it was going to serve. Instead of having a piece of land and adapting to the environment, Back Bay was able to tailor the terrain specifically to the purpose it was to fill. Since the beginning, Back Bay was built to be full of residential homes. This is why it still remains essentially the same as when it was first constructed: full of homes. There has been some variation over time, with the addition of offices and small businesses, but the area is still mostly residences, single family homes, apartments, dorms, etc.

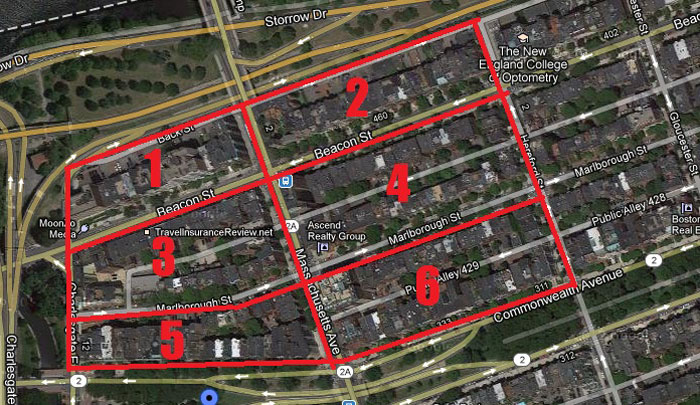

A numbered map, to make references easier to understand. Image via Google Maps .

A numbered map, to make references easier to understand. Image via Google Maps .

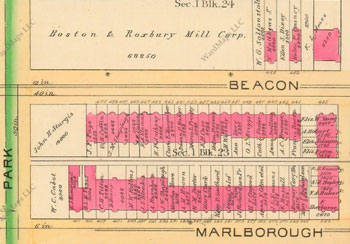

The first signs of my site can be seen around 1887, since the fill plans started in 1880. At this point, blocks 1 and 2 have nothing on them. There aren’t even property line divisions. Being right at the edge of the river, I would have thought that this would be prime real estate, away from the crowd and noise of busy streets. Perhaps, since this time period still greatly relied on water was a source of trade and transportation, living by the river wouldn’t be considered nice either, regardless of the open space and good view. It might be full and busy, as well. For whatever reason, these blocks are completely devoid of activity.

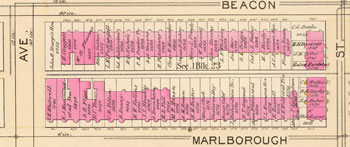

The rest of the blocks have been mostly subdivided into property lines, where the lots are all roughly the same size: long and rectangular, wide enough for just one building. All of the blocks are divided in such a way because “the straight, right-angled system [used in urban construction] simplified the problems of surveying, minimized legal disputes over lot boundaries, maximized the number of houses that fronted a given thoroughfare, and stamped American cities with a standard lot…[this construction method] facilitated buying, selling, and improving real estate” (Jackson, 74). In addition to these standard lots, there are two large lots in blocks 3 and 5. Across the lots that aren’t empty, the proposed structures are all eerily similar.

Sanborn map from 1887

Sanborn map from 1887The maps, luckily, do provide an answer. When the site was first being built, the whole block wasn’t filled at once; it was constructed in pieces. In this particular situation, block 5 was planned until about halfway, at which point they stopped and closed off that small area. Thus, the next set of construction had no street to continue.

1890 :

Over the next couple of years, the site starts to flesh out into the basic plan of what it is today. By 1890, all of the properties have owners and have ceased to just be empty lots, and the plots that do have construction on them are all single-family residences. The whole area looks relatively uniform at this point.

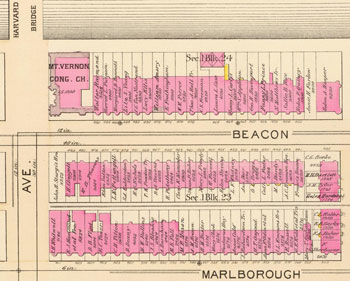

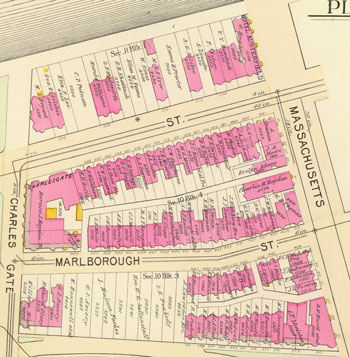

Blocks 2 and 4, 1890 Bromley Map

Blocks 2 and 4, 1890 Bromley Map Blocks 2 and 4, 1895 Bromley Map

Blocks 2 and 4, 1895 Bromley MapHowever, by 1895, the mill is completely gone and has been replaced by a block full of more apartments a church on the corner, the Mt. Vernon Congregational Chruch. There is no visible trace of a mill ever existing in this location—it was completely torn down and replaced. The mill went up and was completely removed in a period of less than 10 years, which is pretty short-lived for a large factory like this.

There are several plausible explanations for its short life span. It could be due to rising cost of rent. As this area becomes more populated and desirable, the land value goes up, and perhaps the mill company simply couldn’t keep up with the cost of holding such large land. More likely, the cause of the mill’s disappearance is due to the rising popularity of electricity around that time. With the advent of electric power and motors, old-fashioned water mills were rendered obsolete. An electric-powered facility could produce more flour in a quicker, and cheaper, manner.

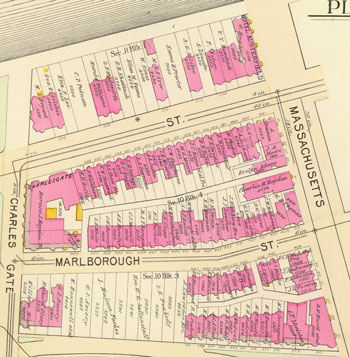

West blocks, 1895 Bromley map

West blocks, 1895 Bromley mapIt is interesting to see the stark differences between the blocks on either side of Mass Ave. The development of the western side of blocks is noticeably slower than its eastern counterparts. Block 1, as mentioned earlier, is completely vacant except for the hotel, and only half of block 5 is filled. The west side also has much larger properties and awkwardly distributed buildings. As you can see, some of the buildings on the western side are line up vertically instead of horizontally.

This disparity could be due to the fact that the east and west sides were not planned the same. The eastern blocks were modeled to be the same as the blocks that came before; the blocks that lead to the Boston Commons. Beacon Street is “patterned after the grand, tree-line boulevards of Baron Georges Haussman in Paris… [they] feature single-family houses with large, carefully tended lawns. [They are] seen as extensions of the developing park system, intended to provide a pleasant pathway from one open space to another” (Jackson, 75). Thus, the eastern blocks, as an extension of the park system (composed of the Boston Commons and the Public Gardens), had to follow suit with exactly how the preceding blocks were arranged. But once Mass Ave was crossed, this continuous path reached an end. Thus, the last blocks were allowed to break uniformity and be different shapes. These western blocks don’t have a straight public alley running all the way down their lengths, since they weren’t as carefully watched and developers were allowed to do work in different ways. All of these factors could influence the popularity and value of the blocks.

There could also be a self-perpetuating cycle of socioeconomic reasons. Being at the very end of the Boston Commons “esplanade,” the western blocks would be the least fancy. The properties would be cheaper and less carefully looked over. The properties are most certainly cheaper, since the lots are much bigger and (in block 5 especially), multiple adjacent lots are owned by one person.

This isn’t to say that the western blocks are low-class. Quite the contrary, all of these blocks are still owned by what one can assume are white, wealthy patrons. The landlords have names such as Rogers, Mason, Lowell, etc. Being a nice neighborhood, the style of the homes was still, over all, very similar (despite the aforementioned discrepancies).

The street-facing facades are all aligned and uniform, neatly adjusted to be one row. The lots facing the alleys, on the other hand, are a bit chaotic, varying in length and shape. This is due to the fact that “rear areas [back lots] were usually less than 25 feet deep, and the little space that was not built upon was typically rancid, disreputable, and overrun by rodents…most people avoided the back yard entirely” (Jackson, 56). This is where all of the waste lay, and so it was an unimportant and purposefully ignored part of the land. It is funny to note that this was the norm back then, since now, a backyard is a trademark of the ideal American home. A big backyard is crucial and is a sign of higher status. The bigger and greener your backyard is, the better off you are.

1895 :

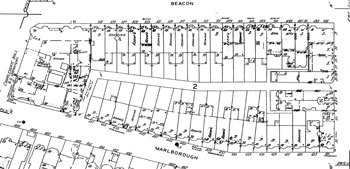

East Blocks, 1895 Bromley Map

East Blocks, 1895 Bromley MapThe larger lots on the Mass Ave side of block 4 have been subdivided. The buildings here are a different shape from its neighbors. They are larger and extend all the way out to the public alley roadway. Instead of leaving this space open, these corner buildings have internalized it into a courtyard-like space that leads to the back alley. The only explanation available for this phenomenon is that methods of taking care of refuse somehow improved, at least enough so that the actual household didn’t have to be so distanced from the back lot. Either this, or the property owner was eager to make the largest building possible. Perhaps, seeing the rising popularity of hotels (two more had been built over the last five years), the landowners planned to create a hotel in the area.

West blocks, 1895 Bromley map

West blocks, 1895 Bromley mapThe Fens must have been really desirable area back in that time, since the properties that face it developed first. Construction starts at Mass Ave, dwindles down as you head down the street, and then is present again at the very end of the street. It’s the middle of that block that’s empty. This phenomenon applied to both blocks 1 and 5.

The western blocks have more hotels than the eastern side, simply because the east blocks are essentially full already. There’s nowhere to put something new. But both blocks 1 and 5 are still half filled. You’d expect block 3 to exhibit this same kind of emptiness, but it is in fact completely filled. This could be due to the fact that block 3 is most similar to the eastern blocks, in that they’re set up the same—with a back alley cutting through the middle of the block. Perhaps it is as simple an explanation as this: the wow-factor had worn off. The excitement for new, shiny things had quelled and, consequently, the land had diminished in value.

1900's :

The rush has definitely ended. The eastern blocks have all but 1 property filled in, whereas block 1 (a western block) has only added 1 building in over 7 years. The stampede for new construction is most decidedly done. From this point on, the evolution of the site is much slower and more subtle. Nothing is torn down or really altered; it’s only subtle changes in usage that are discernible.

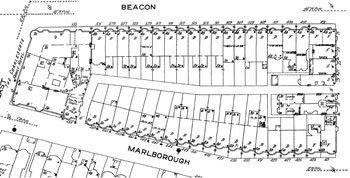

Block 3, 1914 Sanborn Map

Block 3, 1914 Sanborn Map Block 3, 1951 Sanborn Map

Block 3, 1951 Sanborn MapThe sort of change is due to variations of the socioeconomic status of the site. At the start, in the 1880s, the new land was greatly attractive to wealthy patrons. They were business men and important people, and they wanted to move closer to work. The newly filled Back Bay was especially attractive to them, since everything was new and it had already been established as a residential area. As Jackson states, “as a result of [American’s] hostile view of nature…they preferred attached or row houses… a large home on a tiny lot in a densely-settled neighborhood was considered a perfectly appropriate residence for a high-status family prior to 1875” (Jackson, 55). So the site experienced a great period of prosperity. Then the Great Depression hit, and land was quickly dropped and flipped. Then, starting around the 1940s and 50s, with the advent of suburbanization, much of the population let to seek (literally) greener pastures. Americans had decided that they wanted no more of the hectic, dirty city and left en masse to carefully constructed suburbs. They sought smaller, closer, safer communities. And so they left. In their absence, property values dropped.

Throughout this period of change, the homogeneousness of the area was shattered. With such cheap land values, different types of people started moving in. Homes were turned to apartments and flats, and a different social class found the Back Bay suddenly accessible. The most interesting group to move in is the huge immigration of fraternity brothers. I had never given thought to the way a student group could change the community it lived it, but the Back Bay is now filled with these living groups. With the large amount of universities in the area, the fraternities saw the opportunity to live in a nice neighborhood with a beautiful view of the river, whilst being fairly close to any university campus. And that’s how the area (and Beacon Street in particular) came to be filled with fraternities. The large amount of students in the area also means that there are a fair amount of dorms situated here. The larger buildings (hotels and apartments, or particularly wealthy homes), once they were up for sale, were quickly turned into conveniently situated dorms.>

Though Back Bay has seen a lot of change, its essence has not changed. It is still a very nice neighborhood, full of mostly residential areas. For after the turbulence and change, the wealthy patrons returned. And the site is the up-scale mixture that one can see today.

Bibliography

Bromley. David Rumsey Map Collection. Boston: 1890

Bromley, David Rumsey Map Collection. Boston: 1895

Jackson, Kenneth. (1985). Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Boston: 1887

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Boston: 1914

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Boston: 1951